Hi, I’m Chris Walton, author of this guide and CEO of Eton Venture Services.

I’ve spent much of my career working as a corporate transactional lawyer at Gunderson Dettmer, becoming an expert in tax law & venture financing. Since starting Eton, my team and I have completed thousands of valuations for M&A teams, startups, and individuals.

Read my full bio here.

To secure the highest possible valuation in M&A, your business valuation process needs to combine hard accounting data with a compelling narrative.

Valuation methods give you the structure to calculate value, but the narrative comes through in how you apply them: choosing the right comparables, setting defensible assumptions, and showing how intangibles like intellectual property, customer relationships, and growth potential strengthen the case for a higher valuation.

That’s why two companies with nearly identical financials can command very different prices, simply because one told its story more effectively.

In this article, we’ll break down the main valuation methods every deal relies on and show how building the right narrative around them can support stronger outcomes in negotiations.

Need a reliable M&A valuation partner? Eton Venture Services covers all aspects of valuations, from M&A valuations and transaction opinions to goodwill impairment testing. |

M&A valuation is the process of determining what a company is worth in the context of a merger or acquisition. It’s the foundation for shaping deal strategy, guiding negotiations, and supporting due diligence through closing.

Both buyers and sellers depend on valuations to understand a company’s worth, agree on price, and provide boards and stakeholders with a basis for judging the deal’s success.

Here’s how M&A valuation is used throughout the deal process:

Because valuation informs so many stages of the deal, it often draws on multiple methods, supported by expert judgment about the company’s position, growth potential, and strategic fit with the buyer. Below, we cover the most common M&A valuation methods in detail.

Looking for a quick way to gauge your company’s worth? Try our free Business Valuation Calculator and get an instant estimate tailored to your business.

Valuing a company in an acquisition takes more than one lens. Valuation experts look at value from different directions, and each approach highlights something different about the business.

At a high level, every business valuation method falls into one of three categories:

Within these categories are several specific methods that we use in practice. Each brings a different perspective on value and can be more or less useful depending on the company and the deal context.

Here are the key M&A valuation methods you need to know, and how each one works:

The Guideline Public Company Method values a private business by comparing it to publicly traded companies in the same industry. Analysts select a set of “comps” that match the target company in size, growth, margins, and business model, then apply valuation multiples (like EV/EBITDA or price-to-sales) from those public companies to the target.

This method works best when the company being valued has a steady financial history and enough data to line up against public peers. Because public companies tend to be larger and more liquid than private ones, we often make adjustments to account for differences in scale, risk, and marketability.

Suppose we’re valuing a private SaaS company with $8M EBITDA. If a group of similar public SaaS companies trade at an average of 12x EBITDA, then:

Value = 12 x $8M = $96M

(Formula: Value = Comparable Company Multiple × Subject Company Metric)

Applying the GPC Method ultimately relies on expert judgment; first in selecting and adjusting the public comps, then in weighing how the target compares on factors like IP, brand, customer retention, and growth. These judgments determine whether the company should be valued at the higher or lower end of a given multiple range.

Pros | Cons |

Relies on transparent, observable market data. | Truly comparable public companies can be hard to find. |

Captures current investor sentiment and industry trends. | Can be affected by temporary market fluctuations. |

Straightforward to apply once appropriate comps are selected. | Requires careful adjustments for differences in size, risk, and growth. |

The Guideline Transaction Method values a company by looking at multiples paid in recent M&A transactions of similar businesses.

Unlike the GPC Method, which relies on trading data from public markets, this approach reflects what buyers have actually paid for comparable companies in completed deals.

To apply this method, we identify past acquisitions where the acquired companies had a similar size, margin profile, and business model to the company we’re valuing. From there, we apply the transaction multiples, such as EV/EBITDA or EV/Revenue, to the subject company.

Suppose we’re valuing a specialty manufacturing company with $50M in revenue. If recent acquisitions of comparable manufacturers closed at an average of 2.5x revenue, then:

Value = 2.5 x $50M = $125M

(Formula: Value = Comparable Transaction Multiple × Subject Company Metric)

But because no two deals are identical, we adjust for differences in deal terms, timing, and specific circumstances.

For example, one transaction might reflect a premium paid by a strategic buyer for synergies, while another might show a discount from a distressed sale. We factor in that context, assess whether the same conditions apply to the target company, and adjust the multiples accordingly.

Intangibles like customer contracts, technology, or brand strength further influence whether the subject company merits the higher or lower end of the observed multiple range.

Pros | Cons |

Anchored in actual acquisition prices, not just public trading multiples. | Reliable transaction data can be limited or difficult to access. |

Especially useful for valuing private companies where public comps are limited. | Past transactions may not reflect current market conditions. |

Captures the premiums buyers are willing to pay for control or strategic synergies. | Requires careful adjustments for deal terms, timing, and unique circumstances. |

The Discounted Cash Flow Method values a company by projecting its future cash flows and discounting them back to present value at a rate that reflects both risk and the time value of money. In other words, it translates tomorrow’s potential earnings into today’s dollars to arrive at a fair valuation.

We use DCF most effectively with companies that have predictable, recurring revenues, such as SaaS, subscription services, or mature manufacturers.

When we build forecasts, we don’t just project revenue growth and operating costs. We also factor in things like the quality of management, proven efficiency gains, or barriers that protect the business from competitors. These qualitative strengths shape how realistic the growth and margin assumptions behind the model truly are.

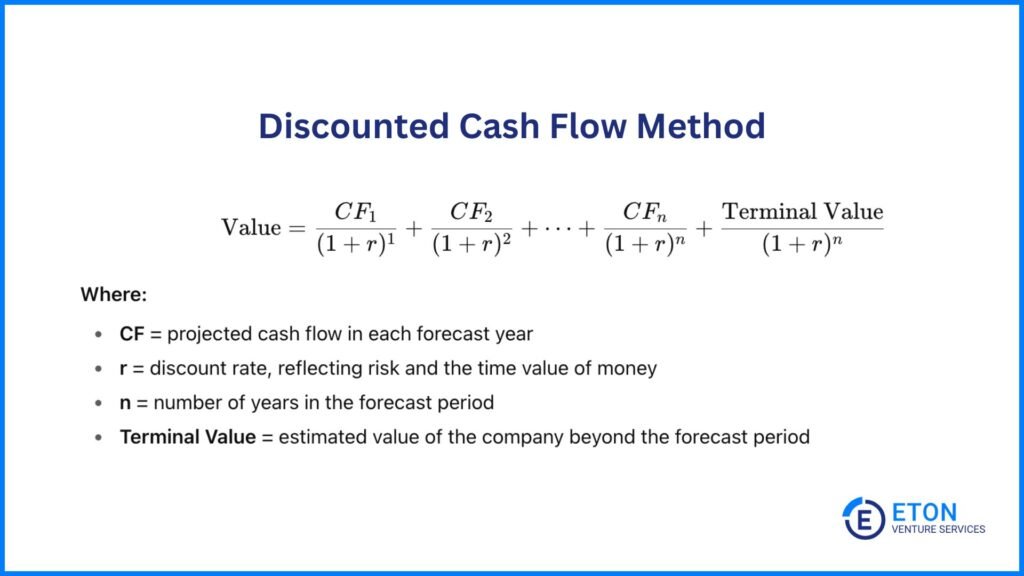

To apply the DCF Method, we use this formula:

Value = (CF₁ ÷ (1 + r)¹) + (CF₂ ÷ (1 + r)²) + … + (CFₙ ÷ (1 + r)ⁿ) + Terminal Value ÷ (1 + r)ⁿ

Where:

Suppose we’re valuing a healthcare services company. We project cash flows of $12M, $14M, and $16M over the next three years, plus a terminal value of $200M. Part of those projections could come, for example, from confidence in the company’s management track record of improving margins and its regulatory approvals that limit competitive threats. We then discount those cash flows at, say, 10%, which brings today’s value to roughly $185M.

The strength of DCF is also its challenge. It gives a detailed, forward-looking picture of value, but it’s highly sensitive to the assumptions behind it. Small changes in projected growth or discount rates can swing the result dramatically. That’s why we always run sensitivity analyses, testing different growth and discount rate scenarios, to see how robust the valuation really is.

Pros | Cons |

Captures future earning potential. | Relies on cash flow forecasts, which can be difficult due to assumptions about growth rates, market conditions, and discount rates. |

Effective for companies with steady growth. | Sensitive to inaccuracies in future projections. |

Focuses on long-term value. | Less reliable for businesses with volatile revenue (e.g. hyper-growth). |

The Net Asset Value (NAV) Method values a company by taking the fair market value of its assets and subtracting its liabilities.

Instead of relying solely on book values, we adjust both assets and liabilities to reflect current market conditions. This can include tangible items like property, equipment, and inventory, as well as intangibles such as patents or licenses, provided their value can be measured reliably.

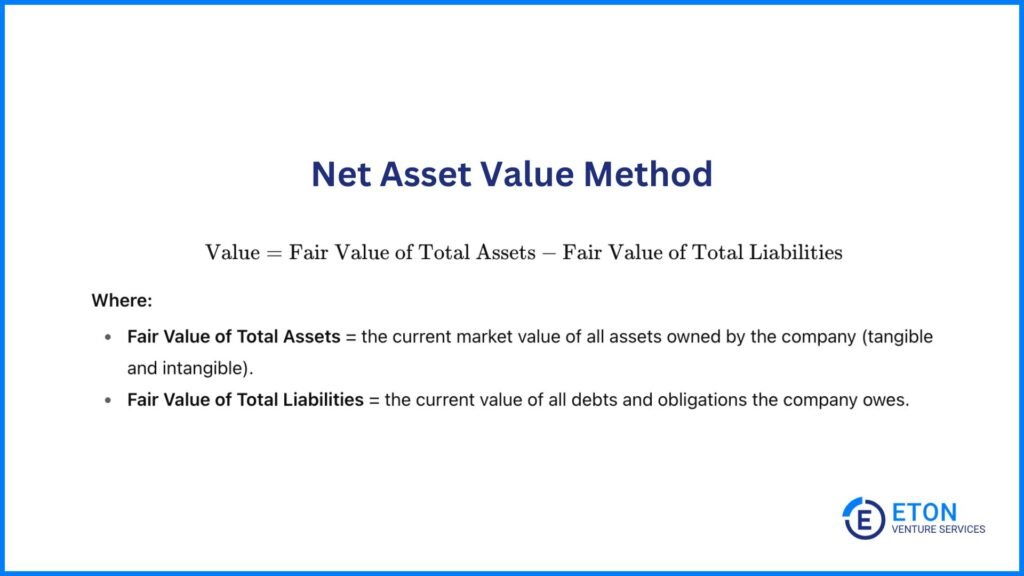

The formula is straightforward:

Value = Fair Value Total Assets – Fair Value Total Liabilities

Suppose a manufacturing company’s balance sheet shows equipment of $20M, real estate of $30M, and inventory of $10M, a total of $60M in assets at book value.

After revaluing at fair market prices, say, the real estate is worth $40M instead of $30M, and the equipment only $18M instead of $20M. That means the adjusted fair value of assets is $68M. Subtract $15M in liabilities, and the NAV comes out to $53M.

While straightforward, NAV has its limits. It gives a clear snapshot of net worth today, but it often misses harder-to-quantify drivers of value like brand equity, customer loyalty, or competitive positioning. That’s why we rarely use it in isolation for M&A. It’s most useful in asset-heavy industries or as a baseline cross-check against income- and market-based methods.

Pros | Cons |

Captures today’s market value of assets and liabilities. | Accuracy depends on the quality of market inputs. |

Useful for asset-heavy businesses (e.g., real estate, manufacturing). | Hard-to-quantify intangibles like brand or customer loyalty are often left out. |

Provides a tangible benchmark or “floor value” for negotiations. | Ignores future income potential and growth, |

The Liquidation Value Method estimates how much cash a company could generate if it were forced to sell all its assets immediately and pay off its liabilities.

Unlike Net Asset Value, which assumes assets are sold at fair market prices, liquidation assumes a “fire sale” scenario; assets may need to be sold quickly, often at a discount.

This method is most relevant when a company is in financial distress, facing bankruptcy, or restructuring. It provides a floor value for creditors and investors, showing what could realistically be recovered if the business ceases operations.

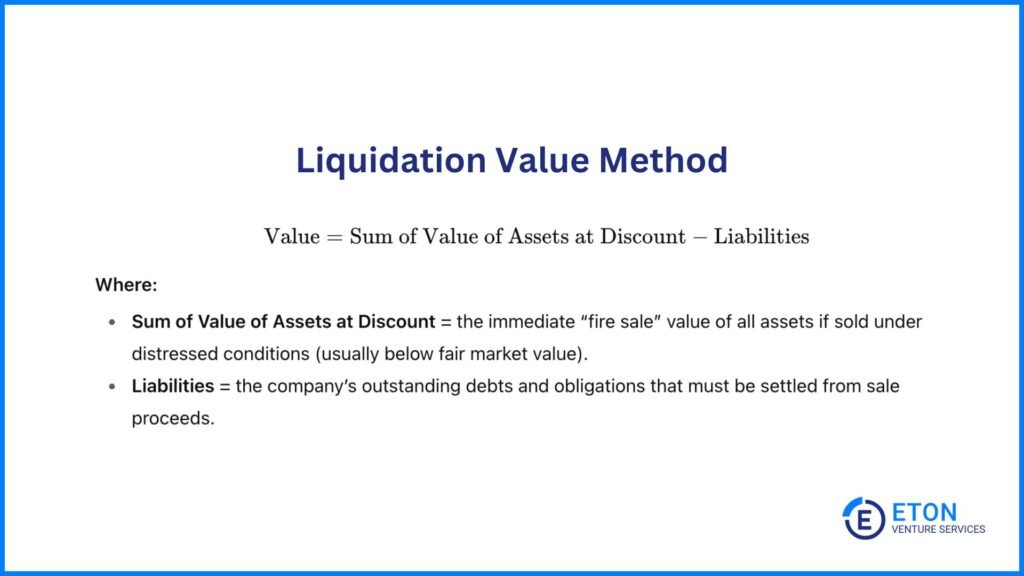

Formula:

Value = Sum of Value of Assets at Discount – Liabilities

Suppose a company owns equipment with a fair market value of $10M, real estate worth $15M, and inventory valued at $5M. In a forced-sale scenario, we might assume the equipment could sell for $7M, the real estate for $12M, and the inventory for $3M-$22M total. Subtract $18M in liabilities, and the liquidation value comes out to $4M.

Pros | Cons |

Provides a conservative “worst-case” value for investors. | Ignores future earning power and going-concern value. |

Useful in bankruptcy, restructuring, or distressed sales. | Asset discounts can be steep and highly variable. |

Clarifies what lenders and investors could recover in a shutdown. | Irrelevant for healthy, profitable companies. |

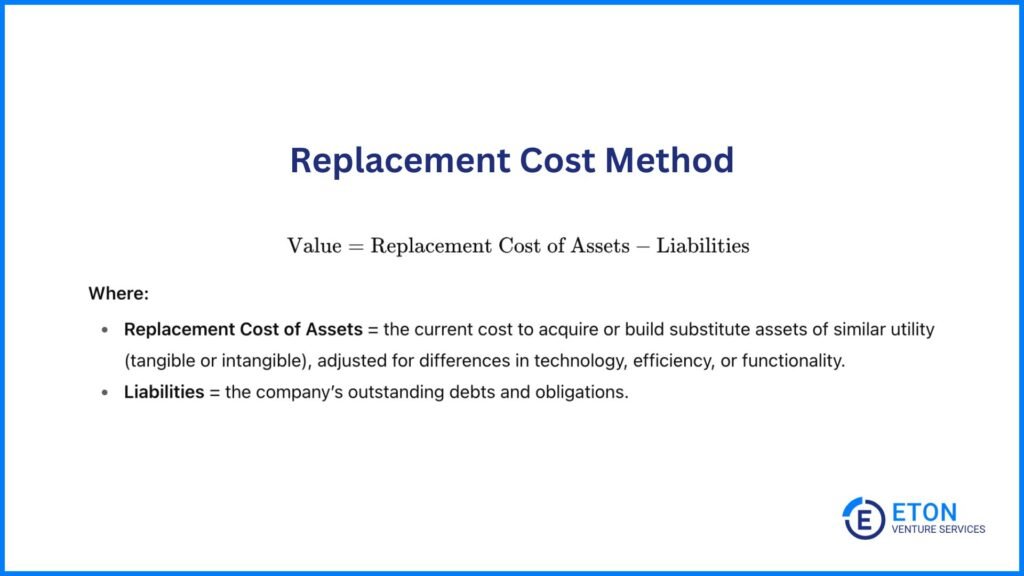

The Replacement Cost Method estimates what it would cost today to replace a company’s assets with substitutes of similar utility. Unlike Net Asset Value, which revalues existing assets, this method asks: “If we had to rebuild this business from scratch, what would it cost?”

It’s often applied to purchased intangibles like software systems, licenses, or proprietary databases, as well as to tangible items such as equipment or buildings. When the substitute differs in technology, efficiency, or functionality, we adjust the estimate to better reflect reality.

Let’s say a company’s proprietary software platform could be replaced with an off-the-shelf system costing $8M.

But since the substitute is less advanced, we add $2M in customization and integration to match the original functionality, arriving at an adjusted replacement cost of $10M. Additionally, its office building might cost $15M to rebuild at today’s construction prices.

Together, the replacement cost of these assets is $25M. Subtract $5M in liabilities, and the replacement cost value comes out to $20M, reflecting the company’s value.

This approach is useful for setting a baseline value, especially in industries where specialized assets can be replicated or purchased on the market. But it has limitations: it typically doesn’t account for the harder-to-replicate advantages of a business, like brand reputation, customer relationships, or management expertise, that often drive premium valuations in M&A.

|

Pros |

Cons |

|

Grounded in observable costs to recreate assets. |

Estimates can vary widely depending on assumptions. |

|

Useful when valuing replicable assets. |

Ignores brand, customer relationships, and other intangibles. |

|

Provides a practical benchmark for the minimum investment needed to replicate the company’s asset base. |

May not reflect the company’s ability to generate earnings. |

Valuing private companies in M&A transactions comes with unique challenges due to the varying quality and completeness of their financial data.

Unlike public companies, which must adhere to strict reporting standards like GAAP or IFRS, private companies often provide less standardized financial statements. This lack of transparency requires a more nuanced approach to valuation.

Typically, earnings multiples or Discounted Cash Flow models are used for private company valuations. However, these M&A valuation methods often need adjustments to normalize financials, accounting for non-recurring expenses and different accounting practices.

In cases where financial data is incomplete, qualitative factors, such as management strength, customer concentration, and market position, become crucial. For instance, a family-owned business with stable, long-term contracts may hold greater value than a public company with less secure relationships.

While obtaining financial data from private companies is possible, especially during acquisitions or formal valuations, accurately interpreting and adjusting this data is essential for a complete understanding of the company’s true worth.

Public companies disclose detailed financial statements, providing a clearer picture of their financial health and simplifying valuation through standardized data.

Conversely, private companies have more flexibility in reporting, leading to less comprehensive financial data. Buyers must conduct thorough due diligence to accurately assess a private company’s worth, often requiring adjustments to normalize financials.

Public companies benefit from real-time market data that reflects market sentiment, making Comparable Company Analysis effective. In contrast, private companies lack this liquidity, leading to a more subjective valuation process based on their unique narratives.

Public companies generally have lower costs of capital due to easier access to financing, which is reflected in their DCF analyses. Private companies face higher capital costs and perceived risks, resulting in elevated discount rates that lower their valuations.

Private companies often experience a “marketability discount,” as their shares are harder to sell compared to public companies. This difficulty contributes to lower valuations, while the ease of trading shares in public markets enhances their valuations.

Financials matter, but they’re just one part of a strong valuation in M&A.

To get the valuation you deserve in an M&A deal, you also need to tell a compelling story about those aspects of the business that make it even more valuable than its current revenue figures suggest.

Let’s say two companies have the same revenue. One sells for twice its revenue (a 2x multiple), and the other for five times (a 5x multiple). Why the difference? Much of it comes down to how well advisors highlight intangibles, goodwill, and premiums that influence the final price.

Unlike tangible assets, these factors don’t always show up in financial statements, but they can be the premium that pushes a valuation higher.

“A common oversight is underestimating the value of brand recognition and intellectual property. Often, people focus on tangible assets like equipment and real estate, while intangible assets such as patents, trademarks, and customer relationships can be equally or more valuable. These assets contribute significantly to a company’s earning potential but can be challenging to quantify accurately.” – Gary Hemming, Commercial Lending Director, ABC Finance Limited

This makes it critical that you have an expert M&A valuation firm on your side — one who can tease out what makes your company more attractive for an acquisition.

Let’s break down the main ways intangibles and goodwill can drive your valuation higher:

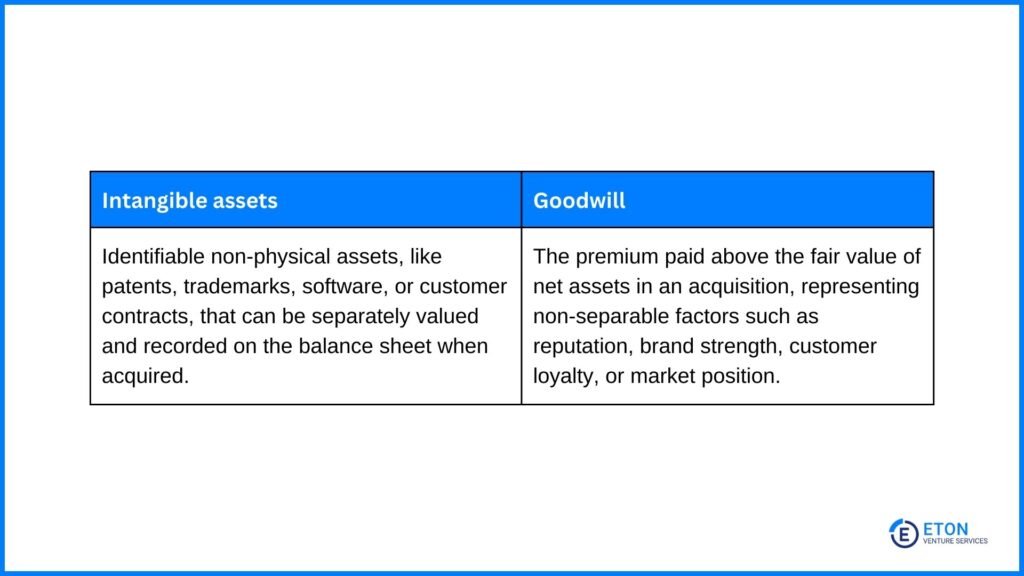

Intangible assets are identifiable, non-physical items that can often be measured and recorded individually in an acquisition. These include things like patents, trademarks, brand recognition, and customer contracts. Because they are separable and more straightforward to value, they often appear directly on the balance sheet in a transaction.

Examples of intangible assets include:

Patents increase valuations because they provide exclusive rights to innovations, which can drive future revenue and give a competitive edge in the market.

However, as Arsalan Ahmed, Strategy & Business Development Manager, Ecovyst, noted when we interviewed him for this piece, there is nuance to including patents in your case for a sale price:

“For instance, initial valuations in a technology acquisition heavily emphasized patents and historical financials. However, further due diligence revealed that the competitive edge of those patents was eroding due to rapid technological advancements. Without assessing the lifecycle of these assets and their relevance in the evolving market, the valuation would have been inflated, leading to overpayment.”

It’s therefore important to incorporate both historical performance and forward-looking elements in your valuation of all your intangible assets.

Having a unique or well-established client base is another way to boost a company’s valuation. For example, if you’re selling a company with a long-term contract with a major corporation, that relationship is often classified as an intangible asset that can be individually valued.

However, the broader context of customer loyalty and the company’s reputation in its industry might contribute to goodwill. These factors are harder to quantify as separate assets but are crucial when buyers assess the long-term growth potential of the company.

A prime example is Microsoft’s acquisition of LinkedIn, where Microsoft gained not just a professional network but also valuable data insights for talent recruitment, positioning itself for future growth.

Goodwill represents the premium paid above the fair value of identifiable assets. It captures broader, inseparable factors, like reputation, leadership, culture, and market position, that influence a buyer’s willingness to pay but can’t be broken out as specific assets.

Examples of goodwill include:

While customer relationships can sometimes be valued as a distinct intangible asset, especially in the case of long-term contracts, the broader reputation and perceived future earnings from customer loyalty often fall under goodwill.

Buyers might be willing to pay a premium because they believe that these relationships will lead to continued success, even though the exact value of these relationships can be difficult to isolate.

According to Dr. Larry Little, founder of the Eagle Center of Leadership, “culture is incredibly important and often overlooked in mergers and acquisitions.” It often plays a role in goodwill, particularly when the acquirer sees value in the leadership style, employee engagement, or company ethos that can’t be captured through financial metrics alone.

Often, disparities in company cultures can lead to resistance, disengagement, and ultimately failure.

A prominent example is AOL’s merger with Time Warner in 2000, where the clash between AOL’s fast-paced, tech-focused culture and Time Warner’s traditional media approach created serious challenges.

This highlights the importance of considering leadership styles and organizational values to maximize benefits in any merger.

The quality of a company’s management team is another intangible asset that can affect its valuation. Effective leaders with a track record of successful decisions can inspire confidence in potential buyers.

A company with a visionary management team is likely to command a higher price. Johnson & Johnson’s acquisition of Actelion benefited from this, as the integration of Actelion’s R&D capabilities strengthened Johnson & Johnson’s market position and delivered enhanced healthcare solutions.

Goodwill may also be influenced by the buyer’s perception of management. A visionary team capable of driving growth or maintaining market leadership can contribute to the premium paid over identifiable assets.

A company’s market position reflects how well it performs relative to its competitors. A business with a strong market position often benefits from pricing power, higher margins, and customer loyalty, all of which contribute to its attractiveness to potential buyers.

Buyers are more willing to pay for companies that dominate their industry, as this leadership suggests lower risks and more stable, predictable returns.

Growth potential is often a key driver of valuation, especially in industries where innovation and expansion opportunities are prevalent.

Companies that demonstrate a clear path for future growth, whether through new market opportunities, product development, or strategic partnerships, are more attractive to buyers.

Beyond intangible assets and goodwill, certain premiums also influence M&A valuation. These premiums reflect specific advantages a buyer gains in a deal that go beyond the baseline valuation of assets or earnings.

Examples of premiums include:

A control premium refers to the extra amount a buyer is willing to pay to acquire a controlling interest in a company, typically more than 50% of its shares. The premium reflects the value of having full control over the company’s strategy, operations, and cash flows, rather than merely a say in how the business is run.

This full control allows the buyer to make significant changes, such as altering strategy, driving acquisitions, or implementing digital transformations, which they believe will create additional value.

The challenge lies in determining where this value is generated. For instance, if a company’s management is in one location but the execution happens elsewhere, deciding how to allocate profits can get complicated.

Barriers to entry make it difficult for competitors to replicate your business. Whether it’s proprietary technology, significant capital investments, or exclusive supplier relationships, these barriers make your company more attractive to buyers.

Amazon’s acquisition of Whole Foods demonstrates this. Whole Foods had a network of premium stores in prime locations, while Amazon brought advanced logistics and a massive online customer base.

Together, they created a powerful synergy, offering faster delivery, seamless online ordering, and efficient inventory management. For competitors to match this, they would need significant investments in both tech infrastructure and a high-end retail presence, raising the barriers to entry.

Barriers like these can be separately identified and valued, but the synergy they create can also enhance goodwill by positioning the company for future success in the market.

Synergies also play a significant role in M&A valuations. When two companies merge, the potential for operational efficiencies, cost savings, or revenue enhancements can significantly impact the valuation.

For instance, if one company has a robust distribution network and the other has a unique product line, the combined entity might achieve greater profitability by leveraging each other’s strengths.

Buyers often factor in these potential synergies to justify paying a premium, believing that the merger will create more value than the sum of its parts.

These synergies may stem from both intangible assets, like a strong product portfolio, and goodwill, such as reputation or market positioning.

The real art of M&A valuation lies in turning qualitative factors into quantitative ones. This is where valuation experts come in. Their job is to take intangible factors like intellectual property, strong customer relationships, and barriers to entry and translate them into numbers that potential buyers can understand.

“The role of a valuation expert is to turn these qualitative factors that contribute to a company’s value into quantitative ones. We put forth an argument that explains why they are high-value assets and should be included in the overall valuation price.” – Chris, Founder at Eton

At Eton, we take a structured yet flexible approach to this process. One simple method we start with is asking clients to provide us with eight bullet points outlining their key achievements and challenges. These insights help us assess the company’s overall trajectory

For example, if the challenges are significant, we might argue that the company is facing headwinds, which lowers our projection of future value and, in turn, reduces the valuation multiple.

On the other hand, if the achievements are substantial, we emphasize these successes to illustrate the company’s growth potential. This could lead to a more optimistic valuation, reflecting the positive trajectory and market opportunities ahead.

The goal is to craft a well-supported argument that explains why these intangible assets should be included in the overall valuation. In other words, it’s about showing buyers the hidden value that might not be immediately obvious from the financials alone.

One of the best ways to boost valuation is by using creative comparables. Valuation experts often search for deals that might seem like a stretch at first glance but can be used to argue for a higher valuation.

For example, let’s say you’re selling a company that generates $10M in annual revenue. A recent acquisition in your industry valued a similar company at three times its revenue. However, there was another acquisition of a different company that sold for five times revenue.

Even though that company might not seem like a perfect match at first, your valuation experts will try to find ways to draw comparisons, arguing that your business has similar growth potential.

“It’s a narrative game. It’s similar to common law tradition. The law doesn’t change, but you need to convince a judge that your set of circumstances and facts fits that law over there in a way the judge just hasn’t previously seen. Often valuations in M&A are more of an art than science because of this.”—Chris, Founder at Eton

This “narrative game” is what often sets M&A valuations apart. It’s about finding ways to make the best possible case for a higher valuation, using a combination of data and creativity.

Now, you might wonder: How can acquirers accurately price assets when future outcomes are highly uncertain? That’s where scenario and sensitivity analyses come in.

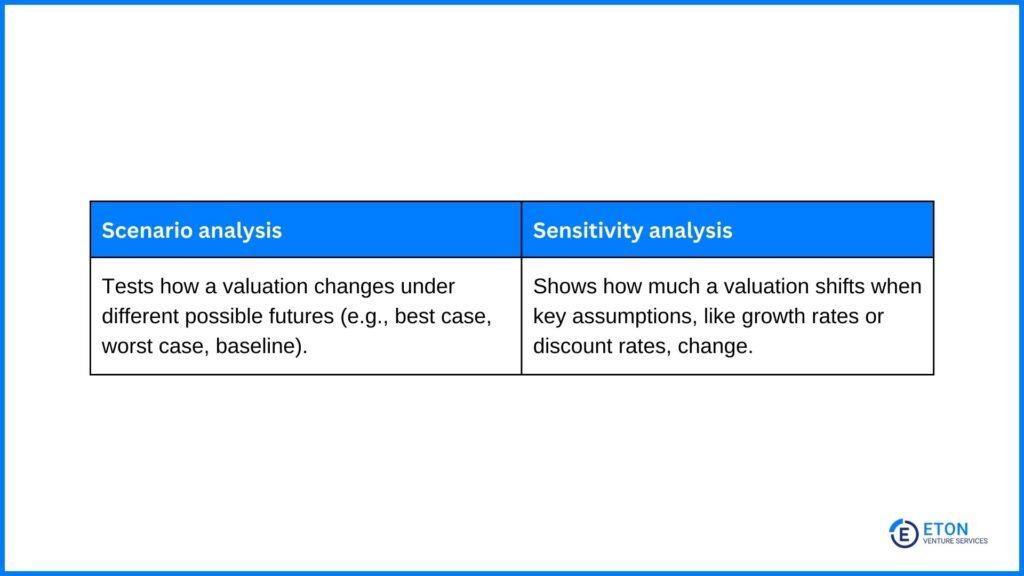

Scenario analysis helps evaluate the expected value of a proposed acquisition or investment by creating various possible future scenarios. This helps in assessing whether a particular outcome is likely to occur.

For instance, in evaluating a target company’s growth potential, an acquirer may construct multiple cases—best, worst, and baseline—all based on assumptions about market conditions, competitive pressures, or operational efficiencies.

The key benefit is that this approach goes beyond static forecasts, allowing stakeholders to understand the full range of risks and opportunities. In M&A deals, this understanding can help acquirers price assets more accurately, especially when future outcomes are highly uncertain.

Sensitivity analysis, a related technique, highlights the most critical assumptions affecting the valuation. For example, small changes in projected revenue growth or cost synergies can have an outsized effect on the deal’s overall worth.

Of course, the effectiveness of these analyses relies heavily on the underlying M&A valuation models used, but they can ultimately inform acquisition structuring and strategic decisions, enhancing the likelihood of successful investment outcomes.

Understanding M&A valuation goes far beyond the numbers, requiring a balance between data-driven approaches and the strategic narrative behind intangible assets and goodwill. This is where firms like Eton make a difference.

Our M&A valuation services specialize in uncovering and maximizing the hidden value in M&A deals by seamlessly integrating quantitative methods with qualitative insights. We don’t just calculate value – we craft a persuasive case for why your business deserves top-dollar consideration.

Our services also include:

Our aim is to bring clarity, strategy, and a compelling narrative to every deal.

Comparable Companies Analysis (CCA) is an M&A valuation method that compares a company to similar businesses using metrics like revenue, EBITDA, and earnings multiples. It reflects real-world data and market conditions, making it useful in industries with many comparable transactions.

However, its accuracy depends on finding truly comparable companies and can overlook unique business strengths, while also being affected by short-term market fluctuations.

The Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) is an M&A valuation technique that estimates a company’s value based on projected future cash flows, discounted to present value. It offers a long-term view of value and is especially effective for companies with steady growth, as it captures future earning potential.

However, DCF relies heavily on assumptions, making it complex and highly sensitive to inaccuracies in projections. This can make it less reliable for businesses with volatile revenues or uncertain growth prospects.

Intangible assets are critical in M&A valuation and can significantly impact a company’s price. These include things like intellectual property, brand reputation, and customer relationships – elements that might not show up directly in financial statements but contribute greatly to value.

Recognizing and effectively communicating the value of these intangibles is key when employing various M&A valuation techniques.

Preparing for an M&A valuation involves several best practices:

Schedule a free consultation meeting to discuss your valuation needs.

Chris Walton, JD, is President and CEO and co-founded Eton Venture Services in 2010 to provide mission-critical valuations to private companies. He leads a team that collaborates closely with each client’s leadership, board of directors, internal / external counsel, and independent auditors to develop detailed financial models and create accurate, audit-ready valuations.