Hi, I’m Chris Walton, author of this guide and CEO of Eton Venture Services.

I’ve spent much of my career working as a corporate transactional lawyer at Gunderson Dettmer, becoming an expert in tax law & venture financing. Since starting Eton, I’ve completed thousands of business valuations for companies of all sizes.

Read my full bio here.

Construction is an industry where one unexpected storm can halt a multi-million-dollar project and a single policy shift can unlock billions in new infrastructure. But much of its volatility, like seasonal demand, is cyclical.

So, when it comes to valuation, you can’t just apply a multiple to last year’s earnings without context. You have to ask: Where is the business in the cycle? Can it withstand a significant downturn? And, how much of its future is already locked in?

As someone who’s valued construction companies across residential, commercial, and infrastructure sectors, I’ve seen how timing, risk, and reliability have a bigger impact on value than last year’s numbers alone.

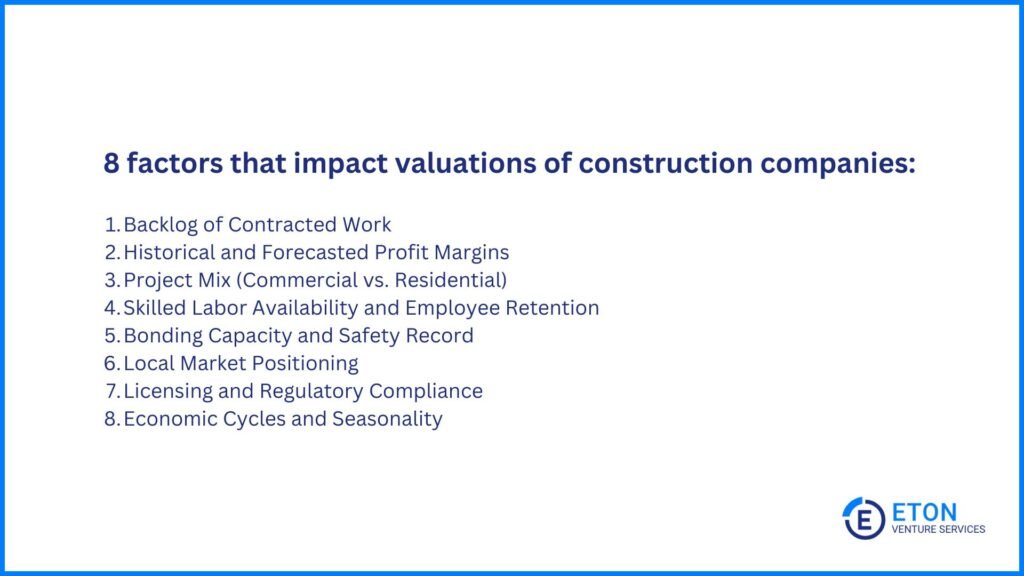

To build a defensible valuation, we look at the full picture; not just what the business owns or earns, but how it holds up over time. This involves analyzing:

These are the traits that drive value. To translate them into a defensible price, you need to apply the right valuation method.

The rest of this article explains how each valuation method works, when to apply it, and what to consider along the way.

Key Takeaways

|

To value a construction company, we typically use one or a combination of the following valuation methods:

Because construction companies vary so much in size, project type, and stability, the right method depends on how the business generates and sustains its income, and how it handles risk across the cycle.

Let’s break down how each method works, when to use it, and what it reveals about your company’s true value.

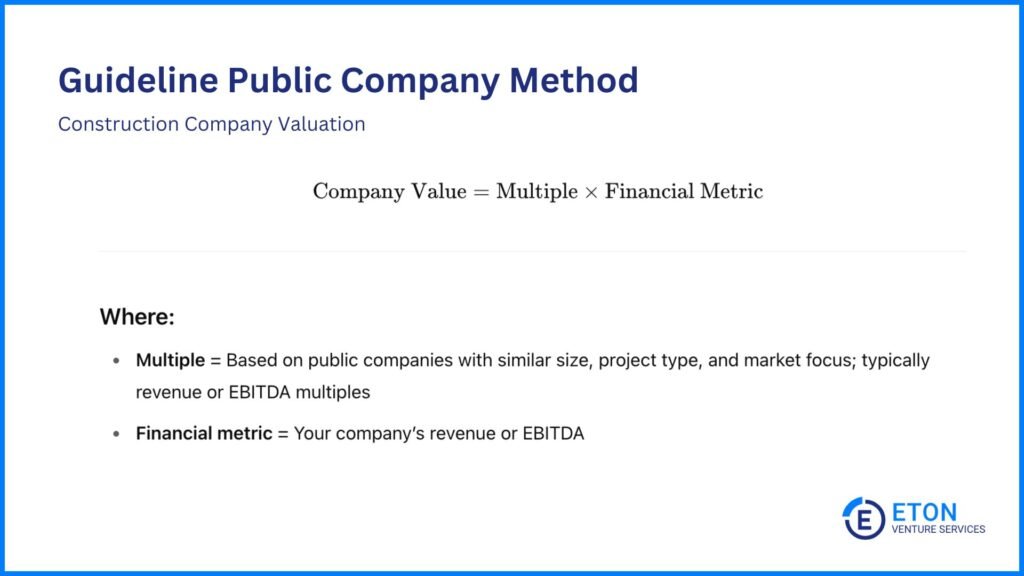

The GPC Method benchmarks your company against public peers to arrive at a fair valuation. It works best for general contractors and subcontractors with enough comparable firms in their region.

To apply it, we identify those peers by their industry classification, size, and project focus, such as commercial vs. residential or specialty vs. general contracting.

After identifying the right comparables, we review their valuation multiples and apply them to your company’s metrics.

Say public comps trade at 1.2x revenue. If your company brings in $25 million in sales, that gives us a value of $30 million.

For construction companies, we typically use one of two multiples:

Tip! You can find these multiples in financial databases, company reports, and online platforms like Bloomberg Terminal that track financial data for public companies.

A strong backlog, solid safety record, and reliable workforce all push these multiples higher. Weak labor retention or poor performance during downturns may push them down.

But these details aren’t always visible in public filings. Instead, we use professional judgment and experience to infer what drove the multiple and assess how your company compares:

Because private companies lack the liquidity and transparency of their public counterparts, we apply a discount to their multiples. Even if the raw multiple is the same, this lack of flexibility and transparency typically lowers the implied value.

Planning a merger or acquisition? Check out our list of the top M&A advisory boutique firms in the U.S. to find expert guidance tailored to your needs.

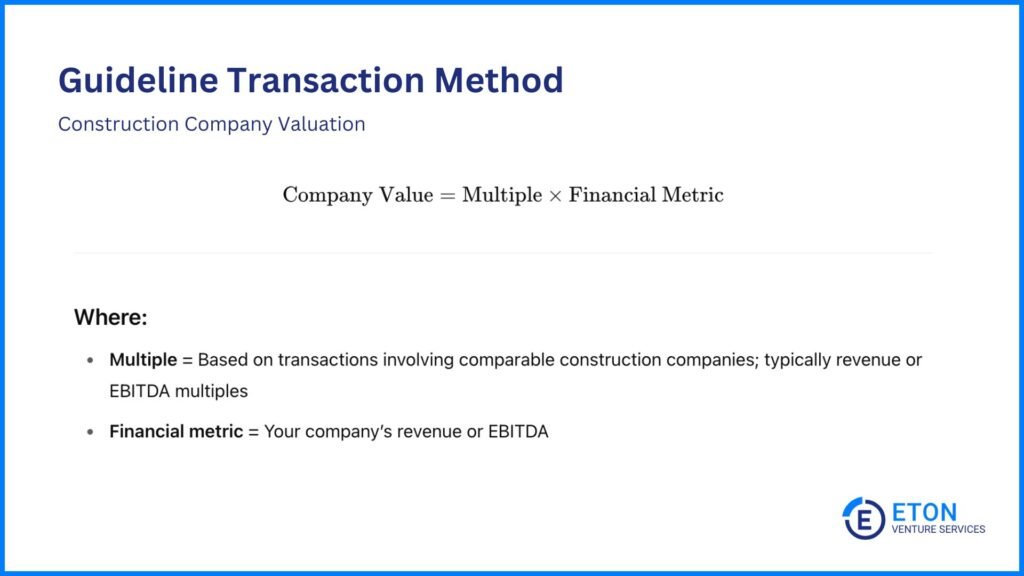

Unlike the GPC Method, which looks at public company stock prices, the GT Method uses actual sale prices from construction company transactions.

It’s grounded in real deals, so you’re not just seeing how investors trade shares, but what buyers actually paid to own a business outright.

To apply it, we look at recent construction company transactions (as long as deal data is available) and narrow in on those involving companies of similar size and service focus. We then pull the revenue or EBITDA multiples from those sales and apply them to your company’s numbers.

For example, if a comparable subcontractor sold for 4x EBITDA, and your company earns $3 million in EBITDA. That points to a $12 million value (4 x $3 million).

Or if another general contractor sold for 0.8x revenue, and your business brings in $20 million in annual sales, the estimated value would be $16 million.

As with the GPC method, we also interpret what drove those multiples and assess how your company compares. If there are meaningful differences, we adjust the multiple accordingly.

For example, if the company that sold had long-term contracts in place and your business doesn’t, we might apply a lower multiple. On the other hand, if your company has a stronger safety record or higher margins, that could support a higher one.

Additionally, we account for deal-specific circumstances. For example, a buyer might have paid more because of expected synergies, while a seller might have accepted less due to pressure to close fast. These details don’t always apply to your business. So we may adjust the multiple to remove those one-off dynamics and reflect your company’s real market value.

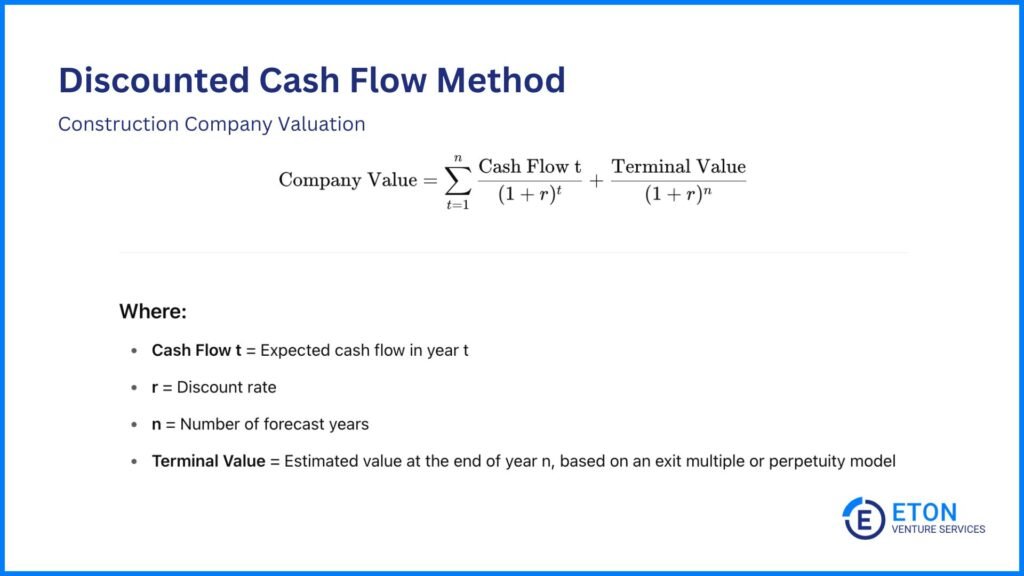

The DCF Method estimates what your company is worth today by projecting how much cash it will earn in the future and adjusting those earnings for risk, time, and growth.

Unlike the GT or GPC methods, which rely on past deals or public stock prices, DCF looks forward. This makes it ideal for construction companies with predictable cash flows and long-term contracts. In other words, we use this method when your backlog is strong, your margins are steady, and you’ve built a business that holds up well through the cycle.

Here’s how it works (with a quick example to make it clear):

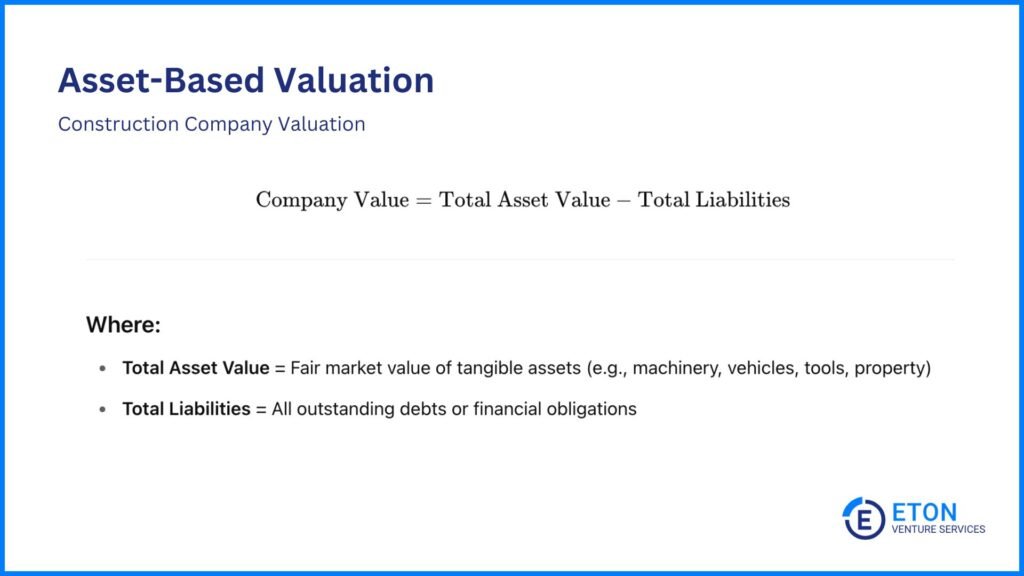

The Asset-Based Approach totals the fair market value of everything your company owns, like machinery, vehicles, tools, and real estate. Then it subtracts liabilities such as debt.

This method works best for construction firms with significant equipment or property, especially when earnings are inconsistent or hard to predict. We see that most with companies that lack long-term contracts, don’t have enough backlog, or rely too heavily on short-term or seasonal jobs.

In those cases, we shift the focus away from future performance and value what’s already there: its tangible assets.

Let’s say your company owns $4 million in trucks, excavators, tools, and land, but has $1.2 million in liabilities. The value using this approach would be: $4,000,000 – $1,200,000 = $2,800,000.

However, this method doesn’t capture intangible strengths like client relationships, reputation, or skilled teams.

So, when a company is asset-heavy but also has value in intangible strengths, we combine more than one valuation model to get the most accurate valuation possible. There are two ways to go about this:

Need third-party valuation help? Explore our guide to the top third-party valuation firms and find the right partner for your business.

Booms don’t last forever, and slowdowns always come around. So when we value a construction company, we pay close attention to how it handles the ups and downs.

The following factors help us analyze this. They tell us whether the business can keep work flowing, maintain margins, and manage risk when conditions change.

As valuation experts, our role is to connect these signals to real numbers and explain how they affect value.

Here’s exactly what we consider and what it tells us:

Backlog shows how much future revenue the company already has in place, typically from signed contracts for work that hasn’t been completed or billed yet.

A large, confirmed backlog means the company has upcoming work and income to count on. This usually leads to a higher valuation because it lowers uncertainty and shows demand is already locked in.

But timing matters, too. If most of that work won’t start for a year, it may not help near-term cash flow. That’s why a firm with $15 million in backlog scheduled to start next quarter may get a higher valuation than a similar firm with $20 million in backlog that won’t begin for another year.

In valuation, revenue tells part of the story. But we also look at how much of that revenue the company actually keeps. Historical and forecasted profit margins give us a clearer view of that.

Strong, steady margins in both areas signal good project management and pricing discipline. Meanwhile, if margins bounce up and down or rely on just a few standout years, it adds risk for the buyer.

For example, a contractor with steady 12% margins year after year is more appealing than one that averaged 15% due to a single standout year but usually operates at 5–6%.

A contractor that builds both housing units and office buildings is better protected from market shifts than one that only does one or the other. This balance reduces exposure to sudden slowdowns in a single market.

Residential projects tend to move quickly but are more affected by interest rates and consumer sentiment. Commercial jobs often take longer to complete, but they bring in larger payouts and can provide steadier income. The ideal is a mix of both, which helps smooth out cash flow and keeps the business more stable across the cycle.

If a company can’t reliably staff jobs then delays and rising costs are sure to pile up.

But when staffing is consistent, projects run smoother, quality stays high, and clients are more likely to come back. It also means the company isn’t constantly scrambling to hire or train new workers. This stability makes the business more valuable in the eyes of a buyer.

Bonding capacity shows how much work a surety company is willing to back the business for. It’s a sign of financial strength, performance history, and reliability. A high bonding limit tells buyers the company can qualify for larger jobs and has a track record of following through.

Safety records matter just as much. Frequent violations or recent incidents raise red flags, while clean audits and strong site protocols give clients, insurers, and buyers more confidence in how the company operates.

In turn, a contractor pre-qualified for $10 million projects, with no major safety issues in recent years, will almost always be valued higher than a similar firm with bonding limits capped at $2 million and a history of claims.

Both bonding and safety reflect how dependable the business is under pressure, something buyers look for when assessing long-term risk.

Construction is highly localized and even national trends don’t hit every region the same way; some local markets stay busy while others slow down.

A company’s ability to handle those shifts often comes down to how well it’s connected to its local market. That means having long-term client relationships, strong ties with nearby suppliers and subcontractors, experience working with local agencies, and a solid handle on permitting and zoning rules.

These connections help the business win repeat work, avoid costly delays, and adjust faster when things change. And when a company runs that reliably, buyers tend to value it higher.

Missing permits, outdated certifications, or past violations can lead to delays, fines, or forced shutdowns, none of which buyers want to inherit.

On the other hand, a company with up-to-date licenses, clean records, and a strong grasp of local regulations signals less risk and fewer surprises. This supports a stronger position in valuation discussions.

All construction companies feel market shifts. What matters is how they handle them.

Some rely heavily on peak-season demand or building booms, which can lead to sharp drops in income during slow periods.

Others stay more stable by taking on maintenance jobs, starting projects at different times, or choosing work that can continue in bad weather.

Companies that build in that kind of year-round stability tend to show more predictable earnings, which makes them easier to value and less risky to buy.

At Eton Venture Services, we provide accurate, independent valuations that support your decision-making, whether you’re planning for growth, preparing for a transaction, or structuring a transition.

Our team of experts is dedicated to offering the highest level of service in assessing the value of your construction company. We ensure that all key factors, such as backlog, project mix, labor availability, bonding capacity, and market positioning are thoroughly considered.

Trust our experts to deliver insightful, tailored valuations that support your next move.

The core valuation methods are similar, but what we look for within the business is different.

General contractors are responsible for managing entire projects, so we focus on factors like backlog size, bonding capacity, project management systems, and relationships with clients and subcontractors. Value often depends on how well they handle large-scale coordination and risk.

Subcontractors are more specialized and usually operate with lower overhead and tighter scopes. Here, we focus more on labor availability, productivity, and repeat business with general contractors or developers. Strong margins, crew stability, and niche expertise often drive value for subcontractors.

Not on its own. One strong year can help, but only if it reflects a sustainable change, like better margins, stronger clients, or long-term contracts that carry into future periods.

Buyers and us valuation experts look for patterns, not one-offs. If that big year was driven by an unusual project or windfall that’s unlikely to happen again, we may normalize earnings to avoid overstating value. But if it signals a shift in how the business now performs, it can absolutely strengthen the case for a higher valuation.

Focus on what reduces risk and improves predictability. Strengthen your backlog with profitable, near-term projects. Build lasting relationships with clients, subs, and suppliers. Keep margins consistent, not just high.

Additionally, make sure your systems are clean and up to date. Minimize key person risk by building a team that can run things without you. And reduce any red flags like safety issues, licensing gaps, or unreliable cash flow.

The more reliable your business looks to a buyer, the higher the valuation tends to be.

Schedule a free consultation meeting to discuss your valuation needs.

Chris Walton, JD, is President and CEO and co-founded Eton Venture Services in 2010 to provide mission-critical valuations to private companies. He leads a team that collaborates closely with each client’s leadership, board of directors, internal / external counsel, and independent auditors to develop detailed financial models and create accurate, audit-ready valuations.