Hi, I’m Chris Walton, author of this guide and CEO of Eton Venture Services.

I’ve spent much of my career working as a corporate transactional lawyer at Gunderson Dettmer, becoming an expert in tax law & venture financing. Since starting Eton, I’ve completed thousands of business valuations for companies of all sizes.

Read my full bio here.

Selling a small, owner-operated business comes with a challenge: how do you show buyers the true earning potential without clouding the numbers with personal expenses or one-off costs?

This lack of clarity can make your business seem less valuable than it actually is—and that’s the last thing you want.

Seller’s Discretionary Earnings (SDE) solves this problem by stripping out owner-specific financial choices to reveal what the business really generates.

It’s the go-to approach for showing a potential buyer how much they can realistically take home from the business.

In this article, we’ll break down how SDE works in practice, why it’s especially important for small businesses, and how you can use it to set the right price tag for your business.

Key Takeaways

|

SDE is a financial metric used to determine the total financial benefit a small, owner-operated business generates for its owner.

It creates a consistent standard that allows buyers to make “apples-to-apples comparisons” between businesses. For example, two businesses might seem to have different profitability simply because one owner takes a higher salary or has loans. SDE adjusts for these factors, enabling buyers to identify which business offers the best potential return on investment.

SDE works particularly well for businesses like restaurants, small retail shops, or service providers, where the owner’s role is integral to daily operations.

And because it effectively highlights exactly what buyers can take home from the business, it’s widely used to value small businesses.

This business valuation method calculates earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA), then adds back the owner’s salary, benefits, and discretionary expenses to determine the business’s normalized profits.

For instance, personal expenses, such as a car lease paid through the business, are excluded so buyers can focus on the cash flow that truly reflects the operations.

The SDE method gets to the heart of what matters most, showing potential buyers exactly what they can take home from the business.

Keep in mind, however, that the SDE method also has its limitations and is not a completely accurate measure of cash flow for buyers post-acquisition. Here’s why:

Given these considerations, it’s important to treat SDE as a rule of thumb rather than a definitive measure of a business’s value.

It’s a useful starting point for understanding profitability, but buyers should work with financial professionals to conduct a deeper analysis. This includes evaluating cash flow, accounting for taxes, and assessing ongoing costs like CapEx and working capital needs to better understand the business’s financial health.

At Eton, our team of experts can help you go beyond the limitations of SDE by analyzing the full financial picture to give you a clearer view of a business’s true profitability.

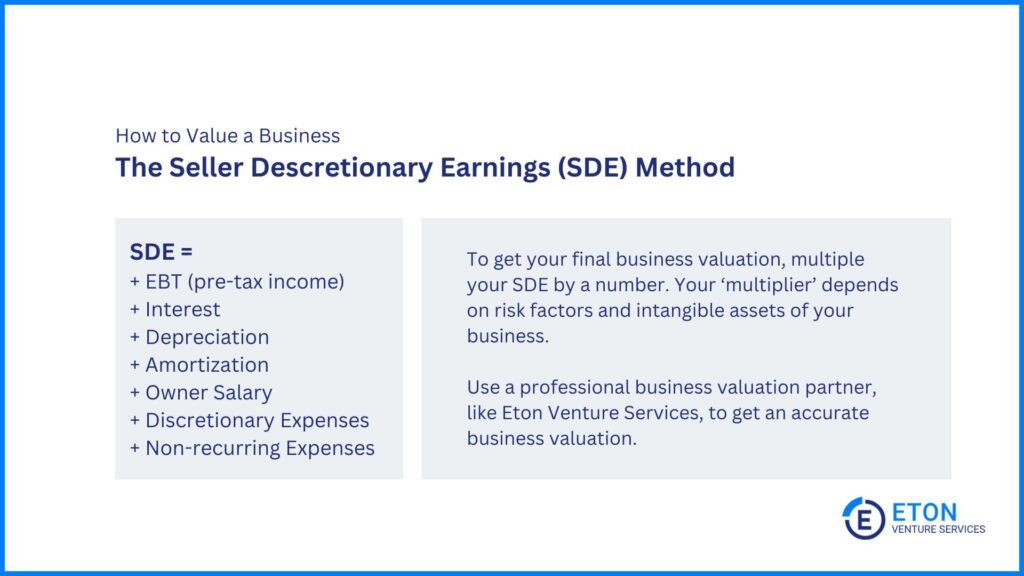

To calculate SDE, use the following formula:

SDE = EBT + Interest Expense + Depreciation + Amortization + Owner’s Normalized Salary + Non-Recurring Expenses + Discretionary Expenses

Each component adjusts the earnings to reflect the business’s normalized profit:

Here’s a step-by-step breakdown of these components to guide you through the calculation process:

Begin with the business’s pre-tax income (EBT), which represents total earnings except for income taxes. Let’s say a hypothetical business’s EBT is $200,000.

Interest expense reflects the cost of debt financing, and the numbers will vary depending on the current owner’s financing structure.

A new owner will likely have a different mix of debt and equity (known as their capital structure), so adding back interest gives a clearer picture of the business’s operational earnings, independent of the current owner’s financing decisions.

For our example, the interest expense is $20,000.

Let’s say your business buys a machine for $10,000, you wouldn’t record the entire $10,000 expense in one year.

Instead, your business depreciates the machine over 5 years, recording $2,000 as depreciation each year. Since this $2,000 reduces the company’s profit but doesn’t involve an actual cash outflow, you’d add back the $2,000 for each year it appears as an expense to reflect the business’s cash-generating potential.

Let’s say that in our example, the machine was fully depreciated. In that case, we’d add back the entire $10,000 to our calculation.

Similarly, if an intangible asset was amortized for a total of $5,000, you would add back the $5,000 to show the true cash flow of the business.

If the owner’s salary is above or below the market rate for their role, adjust it to reflect what someone in the same role would earn in the market.

For example, if the owner’s current salary is $120,000 but the market rate for that role is $80,000, you would adjust it to $80,000 in your calculation.

After this adjustment, add back the normalized salary to the calculation to accurately reflect the business’s earnings without excess compensation or underpayment to the owner.

If the business is run by multiple owners who draw salaries, add back all owner salaries, then deduct the market rate for replacing the second or third owners with a manager.

This adjustment reflects the true earning power of the business if it were to be operated by a single new owner while accounting for the necessary cost of replacements.

Non-recurring expenses, such as legal or consulting fees for one-time projects do not reflect the ongoing costs of running the business.

Add back these temporary expenses to focus the calculation on regular, sustainable earnings.

For example, let’s say our hypothetical business incurred $15,000 in legal fees for a one-time contract negotiation. Since this is not a regular operating expense, you would add back the $15,000 to highlight the business’s true earning potential.

Discretionary expenses —personal or non-operating costs —, such as personal travel, meals and entertainment are not tied to the core operations of the business.

Add back these costs to separate the owner’s personal expenses from the business’s operational performance.

For our example, let’s say the owner spent $10,000 on personal travel that was recorded as a business expense. These costs don’t contribute to the business’s operations, so you would add back the $10,000 to present a clearer picture of the company’s financial performance.

Let’s put it all together now.

Consider a small, family-owned restaurant with the following financial inputs:

Now, let’s apply the formula:

SDE = $200,000 (EBT) + $20,000 (Interest Expense) + $10,000 (Depreciation) + $5,000 (Amortization) + $80,000 (Normalized Salary) + $15,000 (Non-Recurring Expenses) + $10,000 (Discretionary Expenses)

SDE = $340,000

The resulting SDE of $340,000 reflects the total financial benefit an owner can take home from the business, including salary, perks, and personal expenses run through the company.

This figure can also be used by a buyer as an estimate of what they could take home if they assume a similar role and structure as the current owner.

For those who need to calculate Seller’s Discretionary Earnings (SDE) for their business, you can now use our intuitive SDE calculator.

Simply input the relevant financial data, and the calculator will provide an accurate SDE estimate based on your inputs.

for selected period

To value a business using SDE, you apply a multiplier, which typically falls between 1 and 4 for small businesses, to the earnings figure.

Business Value = SDE × Multiplier

While SDE provides a baseline, the multiplier reflects qualitative factors, such as:

For example, a business with stable revenue, strong customer retention, and minimal risks might have a higher multiplier, closer to 3 or 4. Conversely, a business in a declining industry or with inconsistent earnings might have a lower multiplier, around 1 or 2.

So, let’s use our previous example and say your calculated SDE is $340,000, and the market suggests a multiplier of 2.5 for businesses in your industry.

Business Value = $315,000 × 2.5 = $787,500

In this example, the estimated value of your business would be $787,500.

Since the multiplier depends on many factors and can be tricky to determine, we recommend working with valuation experts to refine it based on your specific circumstances.

At Eton, we help you analyze comparable sales and industry benchmarks to ensure your business is accurately and competitively priced. Contact us to learn how we can help you maximize your business’s value.

Every dollar added to your SDE directly increases your business’s value by its multiple.

For example, if your business sells at a 3.5 multiple, raising your SDE by $50,000 could increase your business value by $175,000 ($50,000 × 3.5 = $175,000).

There are two primary ways to increase your SDE:

1. Increase Revenue

One of the most effective ways to increase your revenue is to raise your prices.

When you raise your prices, nearly all of that increase goes straight to your bottom line. For example, if your business makes $1 million a year and you raise prices by 10%, that’s an extra $100,000 in SDE.

You can also increase revenue by introducing new products or services or selling more of your existing ones. However, proceed cautiously—buyers tend to discount the value of recent, unsuccessful campaigns or product launches.

If you plan to sell within the next three years, focus on strategies that are low-risk and easy to track. For example, use marketing efforts where you can clearly measure the results, like online ads that show how many customers they bring in.

High-risk strategies, such as launching new campaigns outside your expertise or hiring a new sales manager, can strain cash flow and lower SDE and your business’s perceived value.

2. Decrease Expenses

Cutting costs is often faster and less risky than increasing revenue. For instance, renegotiating supplier contracts for a small discount can quickly save thousands of dollars.

Similarly, reviewing your operating expenses—like switching to energy-efficient equipment—can reduce overhead without affecting day-to-day operations.

However, be cautious not to cut too much. Buyers expect proper inventory levels, fair employee wages, and reasonable insurance coverage. Reducing these could make your business less appealing to potential buyers.

Valuing a business using the SDE method may seem straightforward, but accurate results require expertise.

Critical details—like adjusting for owner-specific expenses or choosing the right industry multiplier—can have a big impact on the final valuation. That’s why working with professionals who understand these nuances is so important.

At Eton, our team makes sure that your SDE calculation reflects your business’s true earning potential and aligns with current market trends.

Beyond the numbers, we factor in qualitative aspects, such as growth potential, industry benchmarks, and risk assessment, to give you a valuation that’s both competitive and credible.

With our guidance, you’ll be better positioned to set a price that maximizes your return while standing up to buyer scrutiny.

Contact us to learn more about how we can support your business sale.

Your valuation is usually based on the SDE from the last full year or the trailing twelve months (TTM). However, if your business shows inconsistent results, a weighted average of past years may be used to smooth out fluctuations.

For businesses with steady and predictable growth, buyers may consider the projected current-year SDE or average the last three years’ SDE. The latter could lower the valuation if the business is growing consistently.

The difference between SDE and net income lies in how expenses are treated.

Net income deducts all expenses, including the owner’s salary, personal costs, and taxes, to show the business’s overall profit.

In contrast, SDE adds back these same expenses because they reflect the owner’s personal financial decisions, not the business’s core operations.

By removing these, SDE provides a clearer picture of the business’s cash flow as it would be available to a new owner.

The key difference between SDE and EBITDA is how they handle owner-related expenses and their use in valuations.

SDE applies to smaller, owner-operated businesses and adds back the owner’s compensation and personal expenses to show the cash flow available to a new owner.

EBITDA applies to larger businesses and excludes these adjustments, focusing purely on operating performance before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization.

No, SDE and cash flow are different concepts. SDE shows the total financial benefit available to the owner, including adjustments like the owner’s salary and personal expenses.

Cash flow tracks the actual money coming in and going out of the business, focusing on its ability to cover expenses and maintain operations.

Schedule a free consultation meeting to discuss your valuation needs.

Chris Walton, JD, is is President and CEO and co-founded Eton Venture Services in 2010 to provide mission-critical valuations to private companies. He leads a team that collaborates closely with each client’s leadership, board of directors, internal / external counsel, and independent auditors to develop detailed financial models and create accurate, audit-ready valuations.