Hi, I’m Chris Walton, author of this guide and CEO of Eton Venture Services.

I’ve spent much of my career working as a corporate transactional lawyer at Gunderson Dettmer, becoming an expert in tax law & venture financing. Since starting Eton, I’ve completed thousands of business valuations for companies of all sizes.

Read my full bio here.

Manufacturing businesses often carry the label of being asset-heavy — built on machinery, inventory, and production output. And that’s true, to an extent. Physical assets play a major role in how we measure value, especially when profitability is low or cash flow is inconsistent.

But based on my experience valuing manufacturers across different sectors, that’s only half the story. Tangible assets might make up the backbone of operations, but long-term value often hinges on less visible strengths, like tech, intellectual property, and customer relationships.

The most valuable manufacturing firms combine both: strong physical infrastructure and those intangibles to remain scalable, efficient, and in demand.

To understand their true worth, we need to look at both sides, along with the operational traits that keep the business competitive and growing. This means we evaluate:

And then there’s the market itself:

Even a well-run manufacturing business doesn’t operate in a vacuum. Broader economic conditions like interest rates, commodity prices, or shifts in industrial demand can significantly influence valuation.

Weighing all these factors helps us understand what’s really driving a manufacturing business’s value. To then turn these insights into a concrete number, we use valuation methods.

Here’s how these methods work, when they apply, and what to consider in the process:

Key Takeaways

|

To value a manufacturing business, we typically use one or a combination of the following valuation methods:

These methods take the things that drive your business’s value, like production capacity, pricing power, or supply chain strength, and translate them into specific financial metrics and valuation parameters. This includes market multiples, projected cash flows and discount rates, or the fair market value of physical assets.

Let’s look at how each method works, when to use it, and what it reveals about your company’s true value:

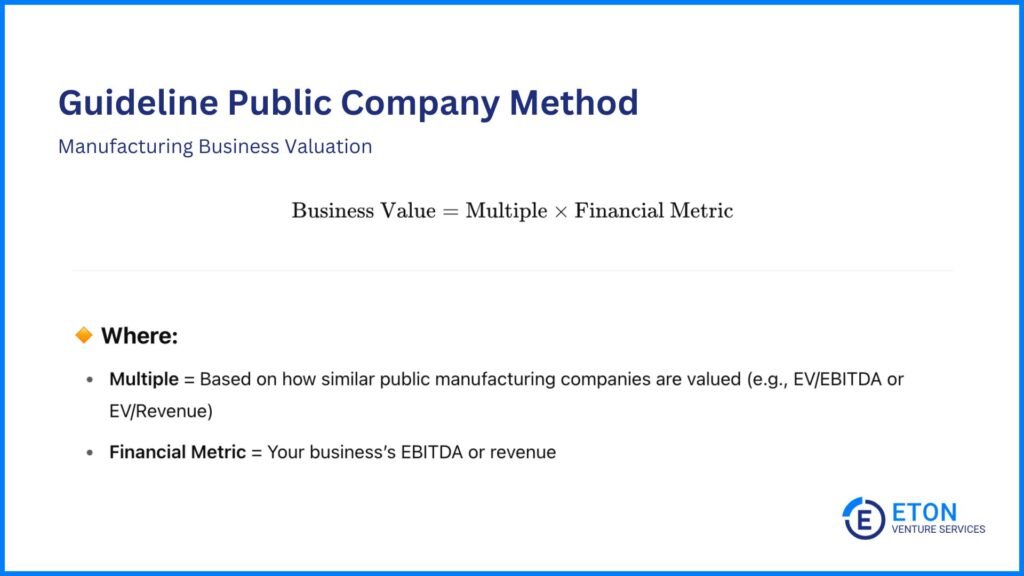

The Guideline Public Company Method compares your business to similar publicly traded companies. Since there are plenty of public manufacturers, from small industrial suppliers to global producers, that gives us a solid set of benchmarks.

From there, we look for companies of a similar size, product type, and business model. Once we’ve identified the closest matches, we look at how the market values them, specifically, the valuation multiples investors pay for them.

Multiples — like revenue or EBITDA ratios — are one of the simplest ways to gauge value. When we apply market-based multiples from comparable firms to your own financials, we can get a realistic picture of your business’s value.

For example, if similar public companies trade at 2x revenue and your business generates $10 million, that would imply a value of $20 million (2 x $10 million).

For manufacturing firms, the multiples we usually look at are:

Tip! You can find these multiples in financial databases, company reports, and online platforms like Bloomberg Terminal that track financial data for public companies.

However, no two businesses are exact matches. Even if the comparables are mostly similar, many of the traits that influence their multiple, like customer retention, operational efficiency, or pricing flexibility, aren’t always clear from public disclosures. So we use professional judgment to interpret what likely drove those multiples and assess how your business compares.

If your firm has lower margins, weaker systems, or a concentrated customer base, we may adjust the multiple down. On the other hand, stronger retention, better operations, or more pricing power may support a higher one.

We also often apply a discount to reflect private market realities. Public firms benefit from greater liquidity and visibility; their shares are easy to buy and sell, and pricing is transparent. Private firms don’t offer the same flexibility, which makes them less attractive to some investors. So, even with a similar multiple, the final value may still be lower.

Planning a merger or acquisition? Check out our list of the top M&A advisory boutique firms in the U.S. to find expert guidance tailored to your needs.

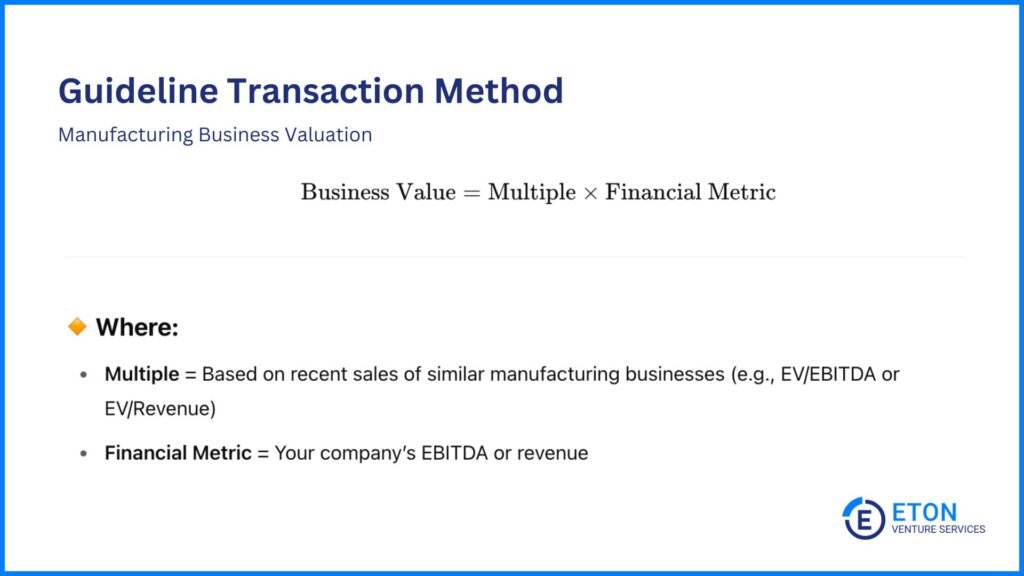

While the GPC Method compares your business to public companies, the GT Method looks at actual sales of similar manufacturers. This makes it especially useful when public comps don’t quite fit or when you want to ground the valuation in real-world deal data.

For example, if comparable manufacturers sold at a multiple of 1.5x revenue and your business generates $12 million, that would suggest a value of $18 million (1.5 x $12 million).

But as with all deals, context matters.

That’s why we don’t just copy a multiple and move on. We look at why the buyer paid what they did and whether that situation applies to your business.

The goal is to filter out the one-time details and get a clear read on what your business is really worth.

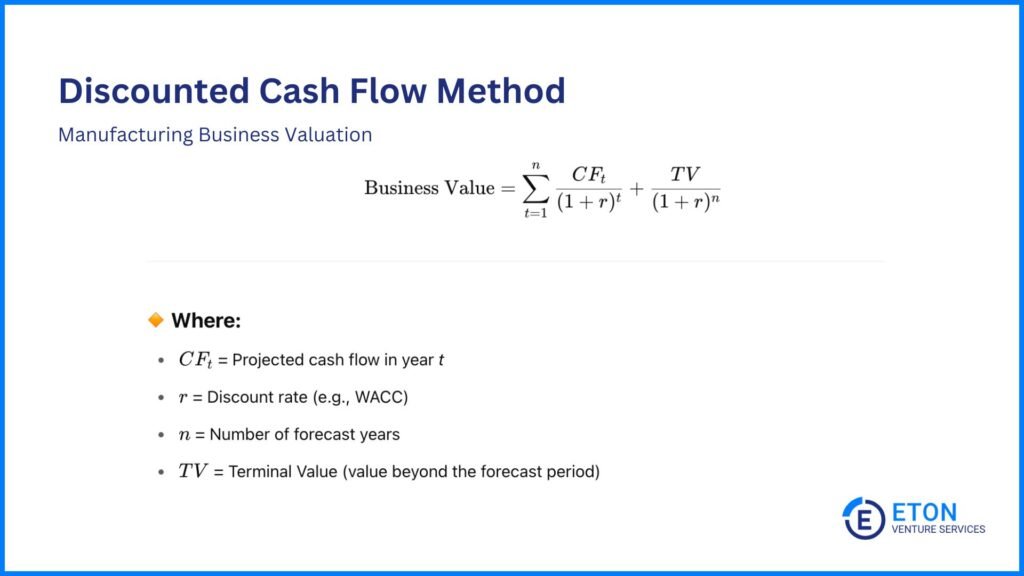

The Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Method forecasts your business’s future cash flows and adjusts for risk and the time value of money.

Unlike the GT Method, which relies on past transactions, the DCF method captures what the company is expected to earn in the future. It’s especially useful for established businesses with consistent and predictable cash flows, as this helps with projecting future financial performance.

Here’s how this method works:

Need third-party valuation help? Explore our guide to the top third-party valuation firms and find the right partner for your business.

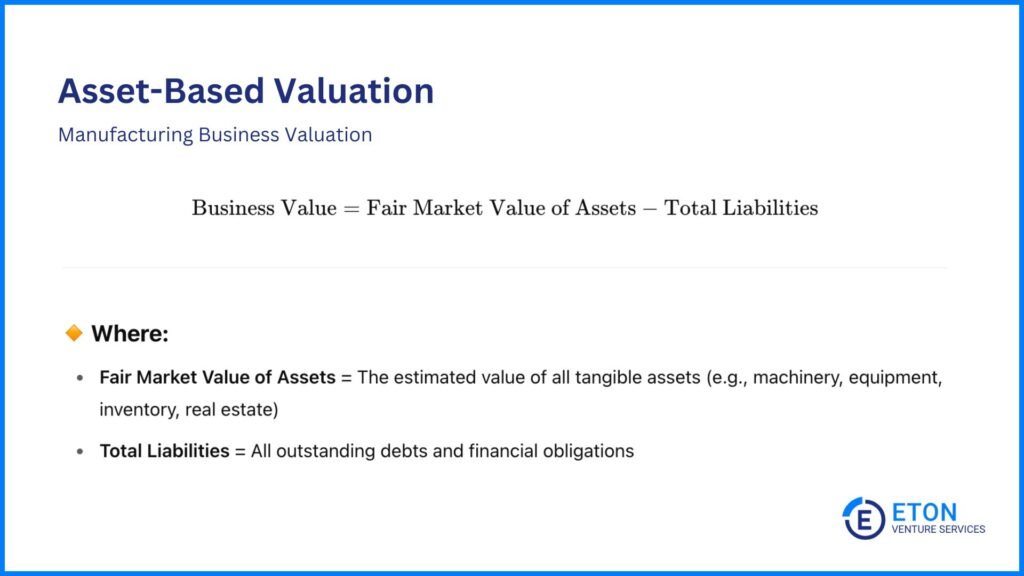

The Asset-Based Approach values the company’s physical assets, such as machinery, inventory, and real estate to determine the business’s worth.

This approach makes sense when the value of tangible assets outweighs the company’s profitability. This often happens when:

When companies buy expensive equipment, they don’t count it all as an expense right away. Instead, they spread the cost over many years through depreciation to account for wear and tear. This depreciation reduces accounting profits.

Also, new equipment might take time to reach full productivity, need training for workers, or be part of bigger growth plans that haven’t paid off yet. All of this temporarily impacts profitability.

And if we only looked at profits, we might think the business isn’t worth much. But looking at the assets shows the true value of what the company owns. The new machines or buildings might not be making money yet, but they’re still valuable and the company could sell or use them differently. Asset-Based Valuation helps us see this value that profit-based methods might miss.

However, the downside of this method is that it doesn’t take into account operational strengths and intangible assets like customer loyalty or intellectual property. For businesses where these factors play a significant role, it’s often best to combine this approach with income-based or market-based methods. There are two ways to do this:

Valuing a manufacturing business isn’t as simple as adding up equipment and inventory. It’s about understanding how well the company can generate cash flow, adapt to market changes, and grow without heavy reinvestment.

Things like production capacity, supply chain strength, pricing power, and technology investments all paint a bigger picture of long-term potential or risk. They explain why two manufacturers with similar revenues might end up with very different valuations.

Valuation experts play a huge role here — we analyze these factors, highlight their impact, and make the case for how they shape your firm’s overall value.

Here are the main factors we consider:

Can the current facilities and equipment handle growth without needing a massive investment?

If a company can ramp up production without a significant cash outlay, it’s in a much stronger position for future growth. This ability to scale without major reinvestment makes the business way more attractive to investors.

I’ve seen this firsthand. A factory with modular production lines that allow for quick adjustments and capacity increases is much more appealing than one with rigid setups that require new buildings or expensive equipment for expansion.

The more a company can grow without heavy spending, the more valuable it becomes, especially during periods of high demand.

How a company manages its inventory and working capital plays a huge role in its ability to generate steady cash flow.

Efficient inventory management ensures two things:

At the same time, managing receivables (how fast the business gets paid by customers) and payables (how efficiently it pays suppliers) is just as critical. It keeps operations running smoothly and maintains strong relationships with both customers and suppliers.

A manufacturing company that turns inventory into cash quickly and keeps a healthy balance between what it owes and what it’s owed shows that it’s a reliable investment.

Buyers and investors always want to know how modern the equipment is and how much longer it will last.

Outdated machinery can lead to inefficiencies and higher repair costs, while modern equipment can improve productivity and reduce operating costs.

But here’s the thing: If a company has recently invested in new equipment, those substantial capital expenditures can put a real strain on cash flow in the short term. This cash flow strain can hurt valuation because it introduces financial uncertainty and potential liquidity risks.

While the new equipment will likely improve performance in the long run, the immediate cash flow pressures may raise concerns for buyers, who often prefer more stable financial conditions.

Buyers also take depreciation into account. This non-cash expense reduces the reported value of assets over time, which lowers reported profits and can affect valuation.

So, while these upgrades improve future performance, investors and buyers weigh how soon they’ll pay off, the short‑term cash‑flow strain they cause, and the ongoing depreciation they incur. All of these factors feed into the company’s overall valuation.

Does your company own its manufacturing space? The answer to this can significantly impact your business’s value.

If a business owns its facility, investors see it as more stable and less risky. They don’t have to worry about fluctuating lease rates or the risk of a landlord deciding to sell.

A well-designed, efficient layout is equally important. It can reduce production costs and improve margins.

Together, ownership and an efficient layout signal long-term control and cost efficiency, both of which can lead to a higher valuation than a rented space with constraints.

Stable demand and a diverse customer base mean the business can reduce the risk of revenue fluctuations and forecast sales with much more certainty. This makes it a safer bet for investors.

On the supply side, having diversified supplier relationships ensures that a disruption with one supplier doesn’t cripple operations.

The business should also be able to adapt to changes in supply or demand to command a higher valuation. For example, if a manufacturing company can quickly adjust production to meet new customer preferences or source materials from alternative suppliers during disruptions, it minimizes operational impact. This makes the business more valuable.

How well can the business maintain margins even when input costs rise? This is often tied to pricing power and customer loyalty.

If the firm has a strong brand with loyal customers, it’s easier to pass on cost increases to these customers without losing them.

Take a laser-cutting tool manufacturer. If it’s known for its exceptional quality and trusted by customers in critical industries, it can raise prices without significant customer loss.

That’s because even if prices go up, loyal customers are willing to pay more because they value the product’s reliability and performance. This ability to protect margins and maintain customer loyalty significantly enhances valuation.

A company that has invested in advanced technology, like automation, or developed patented processes can drastically improve its efficiency, lower costs, and boost profitability.

For example, a manufacturer with a patented production method that reduces waste or saves energy can use this innovation to stand out in the market and charge premium prices.

Advanced technology and IP aren’t just a nice-to-have anymore. They’re key assets that protect the company’s innovations and help maintain a competitive edge. This makes the business far more appealing to buyers and investors.

In industries like manufacturing, there are often strict rules around safety, emissions, and labor practices. A company that’s fully compliant reduces its risk of fines, shutdowns, or damage to its reputation. This reassures investors that the business is well-managed.

If your firm is certified for ISO standards or adheres to environmental regulations, it will likely command a higher valuation because it can avoid legal risks and maintain smoother operations.

Internal factors alone don’t shape the valuation of manufacturing businesses. Broader economic factors like interest rates, inflation, and consumer spending can also greatly affect your business’s value.

For example, when interest rates rise, it becomes more expensive for customers (whether businesses or consumers) to borrow money. This can reduce their purchasing power, which lowers demand for manufactured goods.

The timing of your sale makes all the difference here. Selling during a period of high interest rates might lower the valuation, while selling when rates are lower might lead to a higher return.

Market cycles also play a role. These cycles reflect the natural ups and downs that industries go through, driven by changes in supply, demand, and external factors like economic shifts or technological advances.

For instance, a manufacturer in the automotive sector might see its valuation drop during a period of economic contraction when car sales slow, but its value could soar during recovery when demand for new vehicles picks up.

Companies that can adapt to these cycles, whether by diversifying product lines, entering new markets, or improving efficiency, tend to maintain or increase their value and are by far more attractive to investors.

At Eton Venture Services, we provide accurate, independent valuations that support your decision-making, whether you’re planning for growth, preparing for a transaction, or structuring a transition.

Our team of experts is dedicated to offering the highest level of service in assessing the value of your manufacturing business. We ensure that all key factors, such as production capacity, inventory, working capital, asset condition, demand and supply, technology, and more are thoroughly considered.

Trust our experts to deliver insightful, tailored valuations that support your next move.

Yes. If your product line is heavily skewed toward low-margin, commoditized items, it may reduce perceived value, even if volume is high. A more diverse or higher-margin product mix typically improves profitability and lowers risk, both of which increase valuation.

It depends. Outsourcing that improves margins and keeps quality high can be a strength. But if it creates supply chain risk, reduces control over quality, or makes you vulnerable to geopolitical factors, it may lower your valuation. Buyers often assess how easily outsourced processes can be brought in-house if needed.

In energy-intensive industries, buyers pay close attention to energy efficiency. Companies that have optimized power use or invested in renewable energy may be valued higher.

Likewise, businesses with strong sustainability practices can appeal to ESG-conscious buyers or investors.

If your business is highly seasonal (e.g., tied to agriculture, construction, or holidays), predictable fluctuations may not be a problem, especially if working capital is well managed. But irregular, unpredictable seasonality can introduce cash flow uncertainty and impact valuation.

Yes, in many cases. Buyers view certifications like ISO 9001, 14001, or industry-specific accreditations as proof of quality, consistency, and regulatory compliance. They reduce their concerns and improve valuation, especially if your business serves regulated or global markets.

Schedule a free consultation meeting to discuss your valuation needs.

Chris Walton, JD, is President and CEO and co-founded Eton Venture Services in 2010 to provide mission-critical valuations to private companies. He leads a team that collaborates closely with each client’s leadership, board of directors, internal / external counsel, and independent auditors to develop detailed financial models and create accurate, audit-ready valuations.